In the exhibition ‘Safe Spaces – the right to space in the city’, we demonstrate with examples that in countless places in the city, various groups are fighting for visibility, acceptance and protection.

During the week of Pride Amsterdam, from 31 July to 8 August 2021, we will take a bird’s eye view of examples of queer facilities for the L.G.B.T.Q.I.A.+ community in Amsterdam from the 20th century onwards.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, queer facilities have openly existed in Amsterdam. Visiting those places was not entirely without risk, as evidenced by the recently discovered ‘gay lists’ that the municipality of Amsterdam still utilised aer the Second World War. Those on such lists had considerably less chance of getting a job. Initially, gay-organisations such as the COC (Culture and Recreation Centre, 1946) focused primarily on ‘integration’, or adaptation to a heterosexual environment.

From the 1970s, the focus shifted towards preservation and development of an individual identity. As a part of that, gay and lesbian owned bars, hotels, and various other venues proliferated in Amsterdam in the 1970s and 1980s. These spaces also inspired graphic and print design legacies and boosted nightlife. Today, Amsterdam’s reputation as a LGBTQIA+ friendly city is fading.

The number of reports of violent incidents has been on the rise for several years. Especially, transgenders and bicultural LGBTQIA+ persons have to deal with rejection or expulsion from their direct surroundings, society, and sometimes even by the community itself.

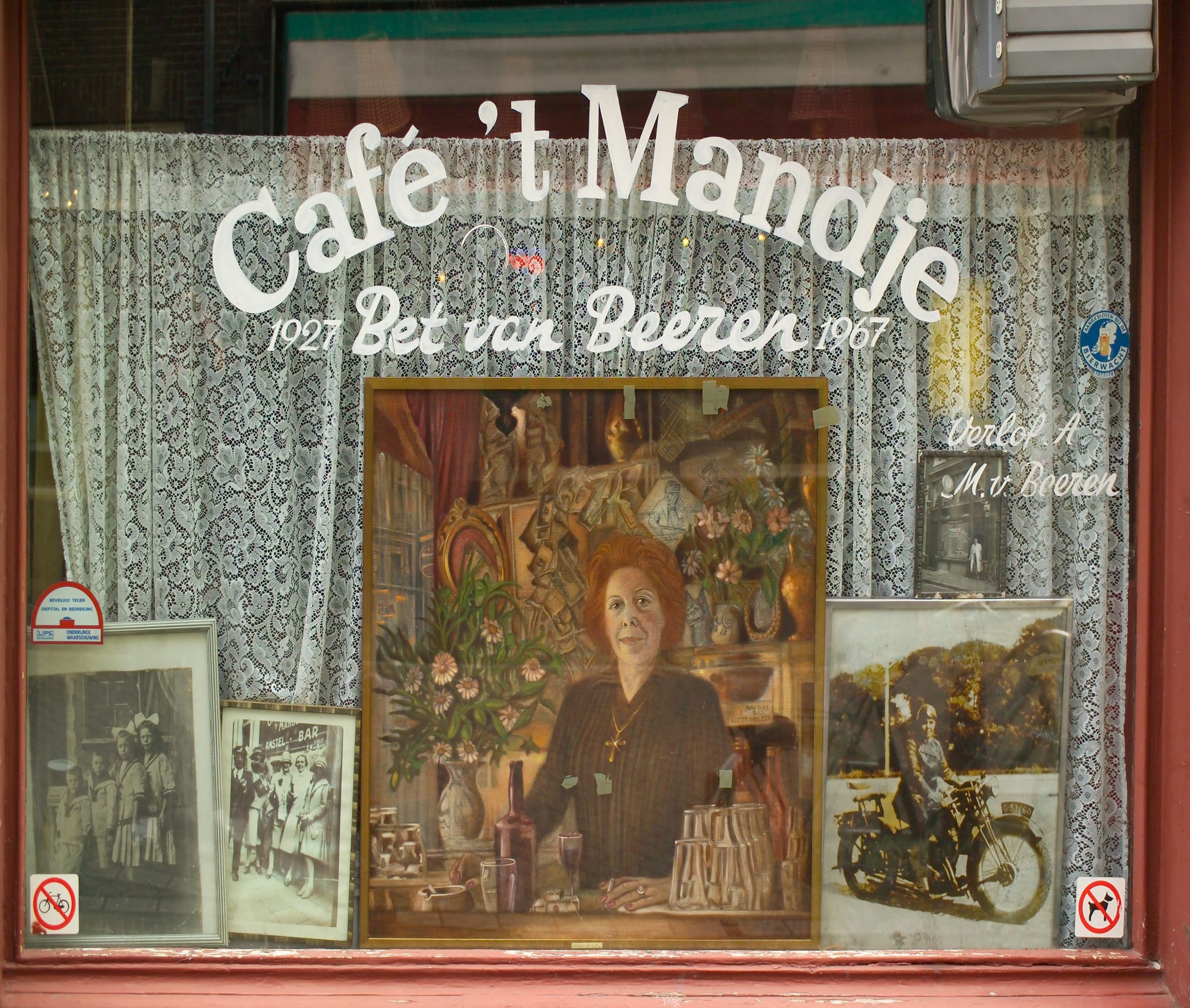

Café 't Mandje, 1927

Bet van Beeren was one of the first women in Amsterdam to openly come out as a lesbian. Beginning from 1927, her bar became a place where the queer community could freely congregate. Café ‘t Mandje thus became an important symbol in gay history and is part of the Canon of Amsterdam as a sign of the city’s tolerance over the centuries.

COC, 1946

The COC (Culture and Recreation Centre), founded in Amsterdam in 1946, is the oldest surviving LGBTIQA+ organisation in the world. It is committed to equal rights and acceptance of LGBTIQA+ persons in the Netherlands and abroad. In the first decades of its existence, the COC focused on arranging shelter and social activities for lesbian women, gay men, and bisexuals.

In Amsterdam the COC operated a successful social club and dancing bar, De Schakel. Benno Premsela (chairman from 1962 to 1971) was the first openly gay activist to appear on Dutch television

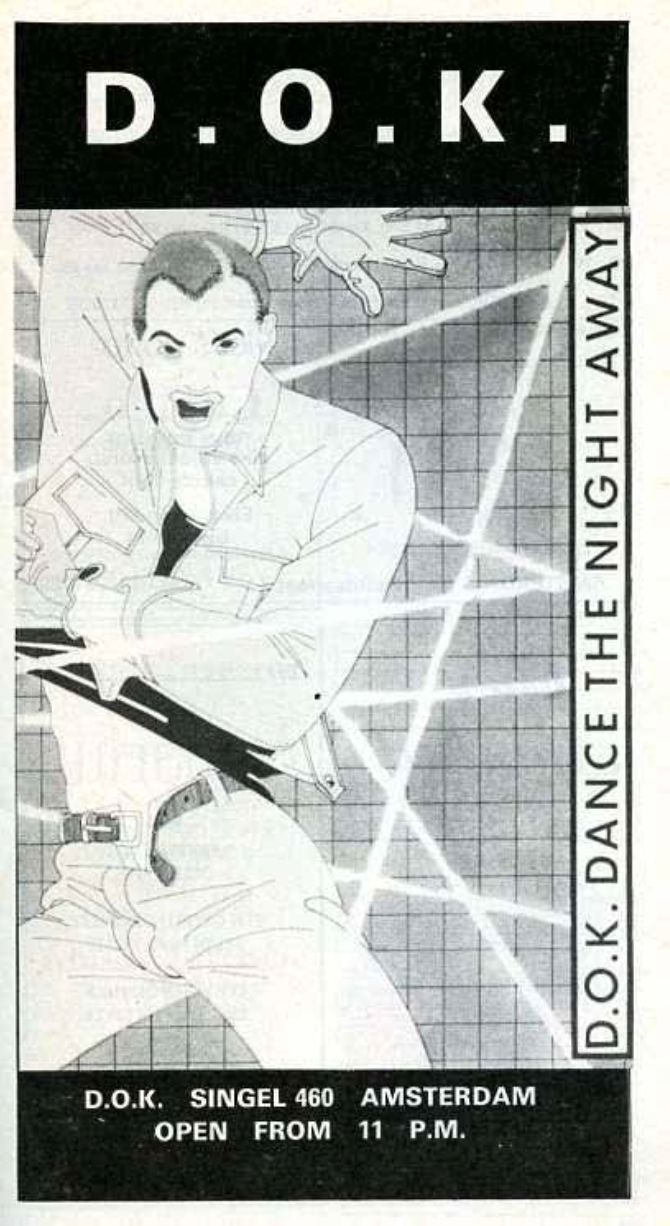

D.O.K., 1954

The DOK was one of the first, and for many years, the largest gay disco in post-war Europe thus contributing to the Amsterdam ‘s position as a gay capital. A_er an internal quarrel, DOK continued independently and the COC opened another illustrious bar-dancing, De Schakel.

Both clubs dominated gay Amsterdam’s nightlife for over 20 years. DOK was more known for a hedonistic reputation that led to the corruption of its o_cial name ‘De Odeon Kring’ and later ‘De Odeon Kelder’, into ‘De Oude Kringspier’. The DOK enjoyed great fame with both the local and international gay scene until it closed its doors In 1989.

Gay and lesbian owned bars, hotels, and various other venues proliferated in Amsterdam in the 1970s and 1980s. Separate women or men only policies permeated this landscape, and restrictions to entry included dress codes (leather or fetish cruising bars) as well as ethnic profiling.

While it can be argued that these exclusionary policies are only indicative of their time, such practices unfortunately continue to stain the relations between various groups within the LGBTQIA+ community. These spaces however, did provide safety for certain groups in the city, inspired graphic and print design legacies, and increasingly came to reflect some of the diversity that Amsterdam itself holds.

IHLIA, 1978

A history of the safety of the LGBTQIA+ community in Amsterdam is one that is rife with activism, demonstrations, and issues of citizenship, discrimination and struggle for legal equality.

IHLIA, an international heritage organization established in 1978 initially from one small room in the University of Amsterdam, has played a pivotal role in documenting, archiving, and exhibiting that history. IHLIA holds Europe’s largest archive of diverse homosexual, bisexual and transsexual material.

Gay monument, 1984

The Homomonument, designed by Karin Daan, commemorates all those who have been murdered or persecuted (and continue to be) for their sexual preference and/or identity. But it also stands for inspiration and support in the fight for recognition, as well as against oppression and discrimination of the LGBTIQA+ community.

The pink triangle refers to the identifying mark that homosexuals were made to wear in concentration camps during the Second World War. The pink granite triangles on the Westermarkt represent the past, present, and future. The ‘future’ is imagined as a stage for action and points towards the COC-location on the Rozenstraat.

L.A. Rieshuis, 1998

This designed apartment complex composed of seven independent dwellings for gay elderly people was opened in 1998. These assisted living homes resulted from a 1994 study on the position of gay men and women in nursing homes. It showed that gay elderly persons o_en refrain from expressing their sexuality in a regular care home, because they fear not being accepted. The L.A. Rieshuis aims to draw attention to this issue and strives to ensure that homosexual and heterosexual generations can live together in a single house in the future.

Rainbow Stairs Zuidplein, 2021

The canopy above these stairs at Zuidplein is decorated with the colours of the Progress Pride rainbow flag. Its goal is to promote awareness, visibility, and acceptance of LGBTIQA+ people. The Municipality of Amsterdam has taken up the Progress Pride flag since 2020.

The six familiar colour stripes represent life (red), healing power (orange), sunlight (yellow), nature (green), serenity (blue), and character (purple). Five more stripes have been added to this. The colours light blue, pink, and white refer to the transgender flag, while the colours brown and black represent people of colour and those living with AIDS or who have died from the disease.

Exhibition Safe Spaces

These and more examples from the perspective of women, religion and ethnic groups can be seen until 19 September 2021 in the exhibition Safe Spaces – Right to Space in the City. The exhibition can be visited for free at Arcam on the Prins Hendrikkade from Tuesday to Sunday between 13-17 pm.

‘Safe Spaces – The right to space in the city’ is curated in collaboration with researcher and architect Ali T. As’ad (Curatorial Research Collective), Cognizant Digital Business, Dutch Design Foundation, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences and Studioninedots.