If there’s one thing that has become apparent in recent weeks, it’s how quickly our set values and ideas can become outdated. This also applies to architectural concepts. Arcam has begun to take stock of this for further consideration.

‘Amsterdam to embrace “donut” model to mend post-coronavirus economy’. The news in The Guardian is already three months old. At that time—during the peak of the Corona outbreak—it seemed logical to look into this topic more closely, once the post-coronavirus era had arrived. We soon realised that this was a rather naive thought, so we started working on it.

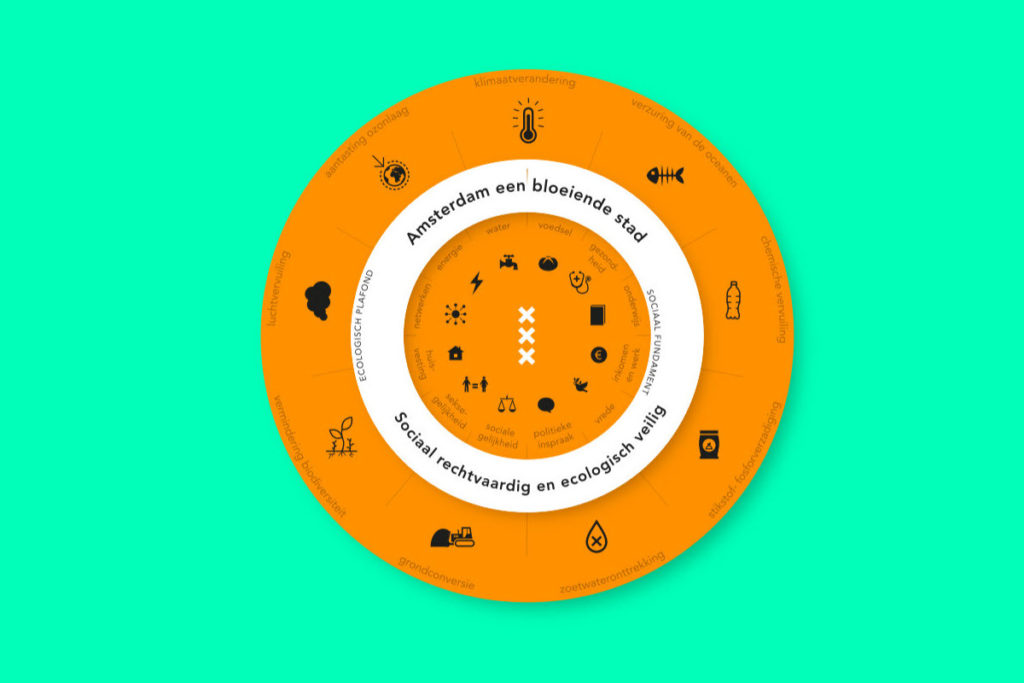

The model by British economist Kate Raworth aims for a circular, sustainable, social city, one which isn’t based on the classic economic model of (financial and spatial) growth, but on (ecological) balance and equality. And although Raworth’s role is important—as a source of inspiration and partner in developing knowledge—the Donut concept is formally taking shape in municipal policy for a circular city 2021–2025, which was adopted on 7 April and will continue into 2050.

But what does Donut City Amsterdam look like? Right now it seems like a lot of good intentions, ambitions, research, (small) cooperatives, and data linked to an implementation agenda (although we haven’t seen a single paragraph about financing). Still missing is a long-term spatial vision, akin to Amsterdam’s General Expansion Plan in the 20th century, or the Compact City concept.

A spatial model anchors and supports the behavioural change that Donut City Amsterdam aims to achieve, but can also help in making really tough choices. How is the Donut City connected to the need for a healthy, affordable housing market, with representation and inclusivity at every level? And what about all those companies that do want to grow and are not yet so circular, but are important to the city?

Perhaps that should begin with another metaphor. We could come up with a different delicacy to bring the image of the greasy, quintessentially American donut into more of a Dutch context. Balkenbrij, for instance: a cheap, particularly nutritious form of upcycled waste made into festive traditional food, from a time when circularity was still commonplace. Or the krakeling, with not one hole but two, within an infinitely circular shape.

To raise the connection to a spatial model, the falafel wrap is likely the most appealing example. After all, in this programmatically healthy, vegetarian, internationally oriented but locally anchored and versatile meal, a variety of ingredients are firmly held together by a neutral but very effective envelope. Just like the Donut City concept should be more than simply policy for circular food and the built environment, but also about the associated overarching design for sustainable, green, healthy, safe, and socially robust neighbourhoods.

We already have the ingredients. That’s mostly just a matter of collecting, weighing, and making the occasional difficult choice. Are we really getting rid of unhealthy companies? Is everyone actually allowed to participate in the city? The basis for the wrap is obvious, and right now we are diligently working on it. The conversation with the city about this is currently in full swing. Let the Environmental Vision for Amsterdam 2050 be the spatial basis for the Donut City.