If there’s one thing that has become apparent in recent weeks, it’s how quickly our set values and ideas can become outdated. This also applies to architectural concepts. ARCAM has begun to take stock of this for further consideration.

A real free space is one that liberates not only the user but also the architect.

After six months of the coronavirus, which unnoticed has become COVID-19, a number of things have shifted. The disruptive power of the virus is slowly becoming apparent worldwide. Architectural recalibration #12: Free space.

Like an unseen assailant, COVID-19 assaults human rights, companies, cultural institutions, educational opportunities, and public images. Bankruptcies, domestic violence, growing inequality, and ongoing insecurity are taking their toll. In the Netherlands, the energetic approach of the Rijkswege, in the form of the findings of the Dutch Health Ministry (which are of course above doubt) and the press conferences by the (incorruptible) triumvirate of ‘Coronaministers’, is wearing thin. In its place are doubtful mayors, insecure enforcement officers, and glimpses into both the private parties of our authorities and the public parties of our younger citizens.

And when authorities lose strength and credibility, new rules and laws are either not understood or trusted. And where we don’t have faith in our environment, the need for free space arises. But this can be positive, too: places that offer space in a world where each individual feels a collective connection with the quality of (everyone’s) life, without any sort of recompense.

Free space has many manifestations. It can be an open-air place, where history and memories are created without the intervention of a designer, like at (music) festivals. It’s a way to go unnoticed, like during Hong Kong’s continuing protests. It’s a political tool when it comes to representing or protecting vulnerable groups or valuable achievements. It can be a policy directive to ward off undesirable processes. Or a safe space where people can talk freely—seeking strength or demanding power.

Since last week, Studioninedots (together with design studio Lesley Moore and architecture journalist Kirsten Hannema) has been involved in just such a conversation with the Wandervoids initiative. The search for a timeless quality of form, without predetermined function, is nothing new in the history of architecture. It’s a high-quality brand of escapism, which every self-conscious designer allows themselves from time to time, but which has acquired a new topicality because we can no longer (really) move freely since the outbreak of the coronavirus.

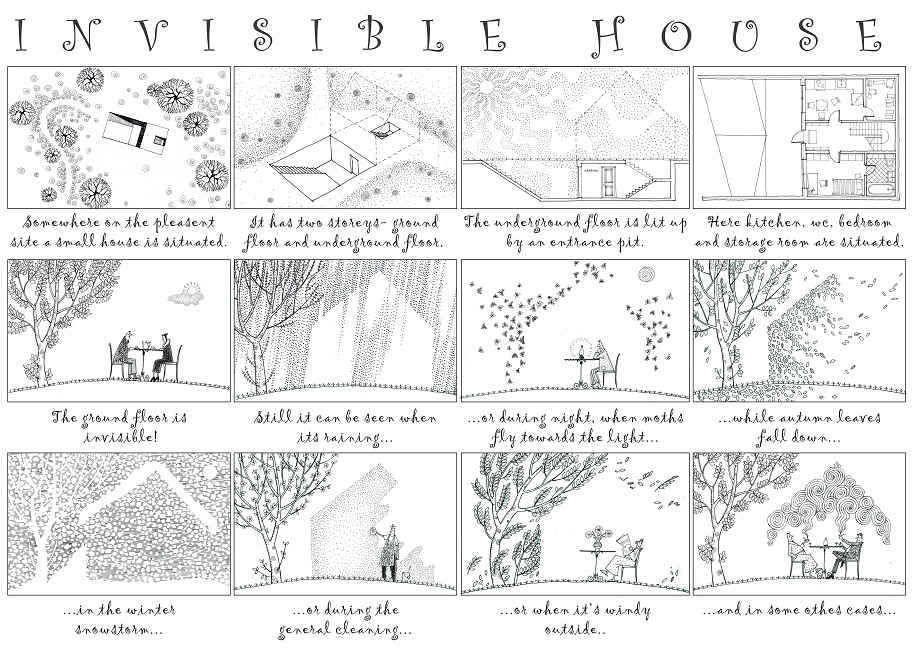

Studioninedots is exploring the possibility of undesigned designed spaces, of emptiness that’s full of meaning, of spaces which have ‘no programme’ as their programme. Especially remarkable is that the agency is looking for ways to actually create such spaces. I’m imagining something like the design for Quiet Time – The Invisible House by a group of young Russian architects. For a competition they created a house that is, in principle, invisible. Unless you clean it. Or if fireflies blunder into it when you switch on a light inside. Or if you smoke in it. A house that only takes on meaning and form when it’s put into use.

A real free space is one that liberates not only the user but also the architect. To deliver this actually requires the ultimate leap of faith for the designer, the client, and the user: the transference of a carefully designed space with all the freedom to internalise, to ignore, and to alter it. Yet where you always seek connection, where you try to understand the other, and on top of that, can trust that they want the best for you. Within all the aforementioned abstractions, we can declare that, for the time being, COVID-19 doesn’t bring free space any closer.